Related

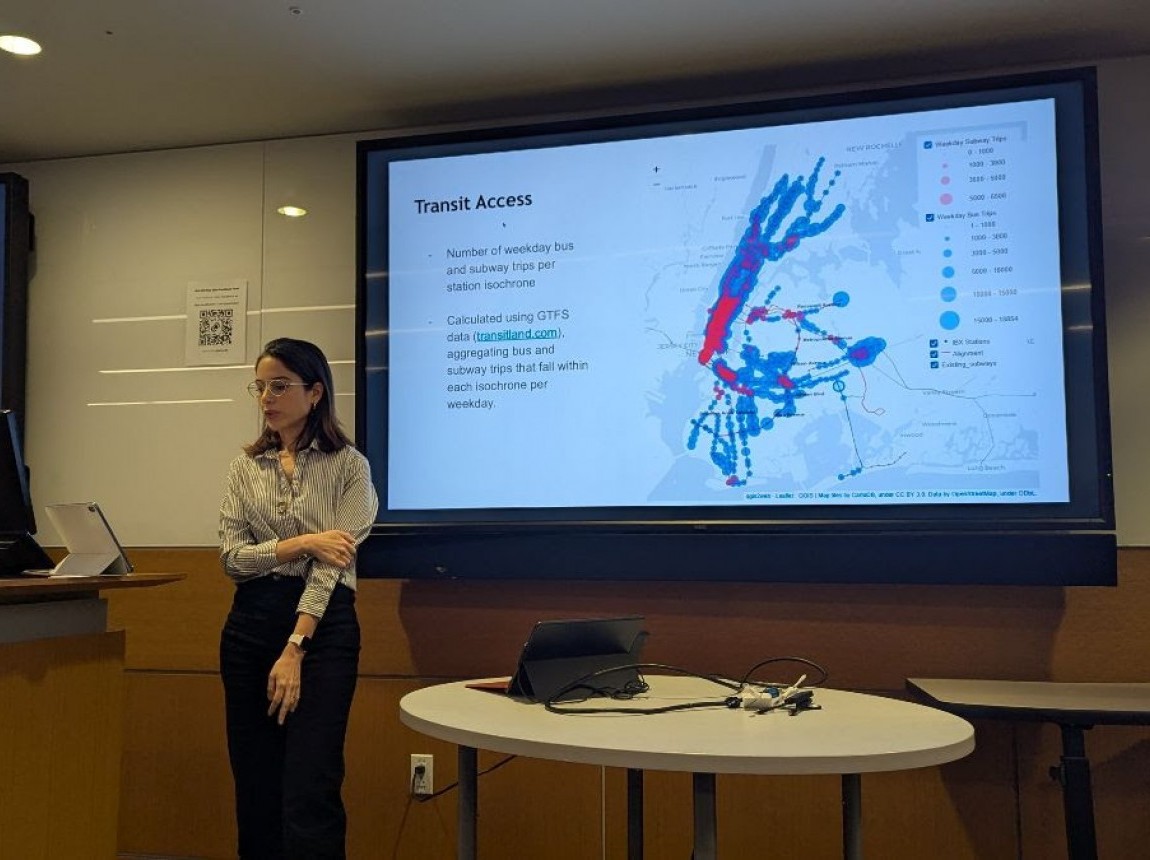

Elif Ensari Presents

Illegal Parking Incidents Research

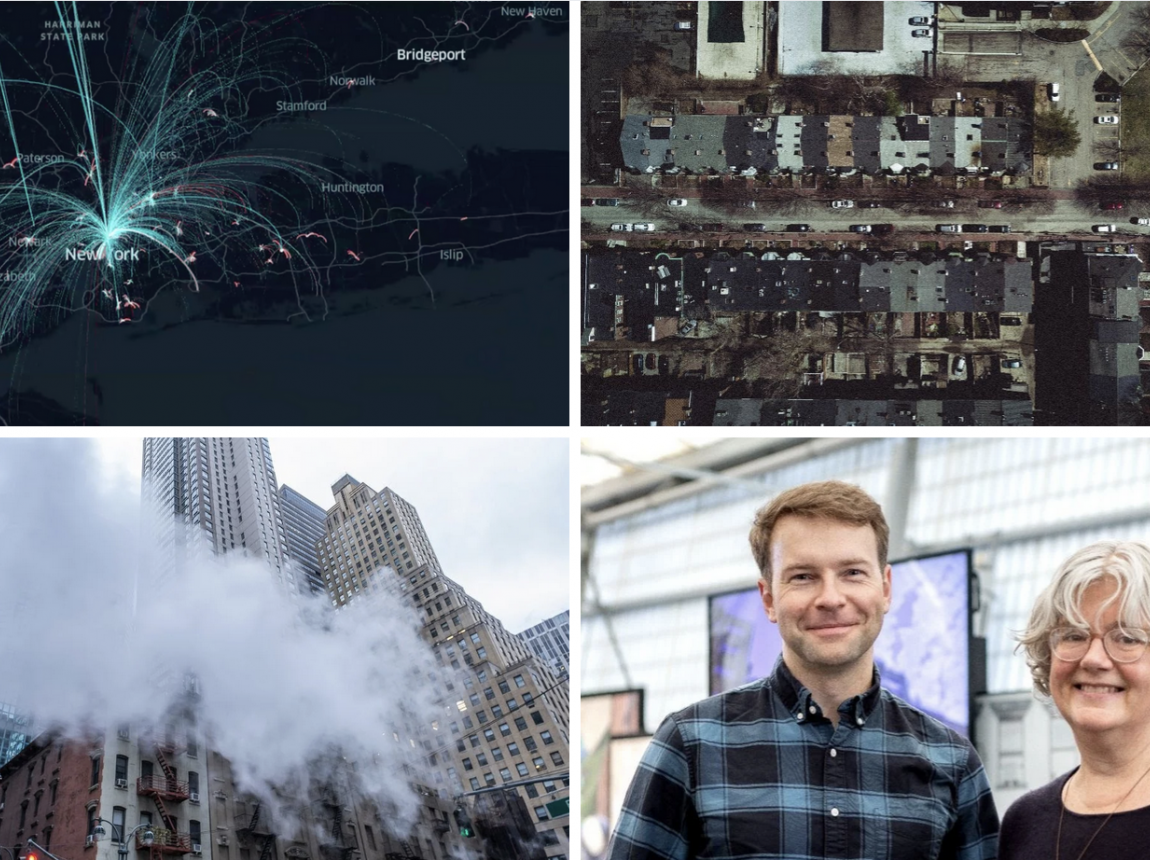

Bartosz Bończak’s CityWorks Contribution

Profiled in NYU News

Eric Goldwyn Makes Case for a NYC Transit Mayor

Transit Costs Project Questions

Two-Person Crews on NYC Subways

Eric Goldwyn Debates Free Buses

on The Brian Lehrer Show

What U.S. Cities Can Learn from Istanbul

on Building Urban Rail

Let’s Make Muni’s 49 Van Ness/Mission Bus Work

for San Francisco

Five Proposals

to Make Government Spending on Transportation More Efficient

Times Square Casino Would Be a Mistake

Should the Bus Be Free?

Transit Advocates Are Divided

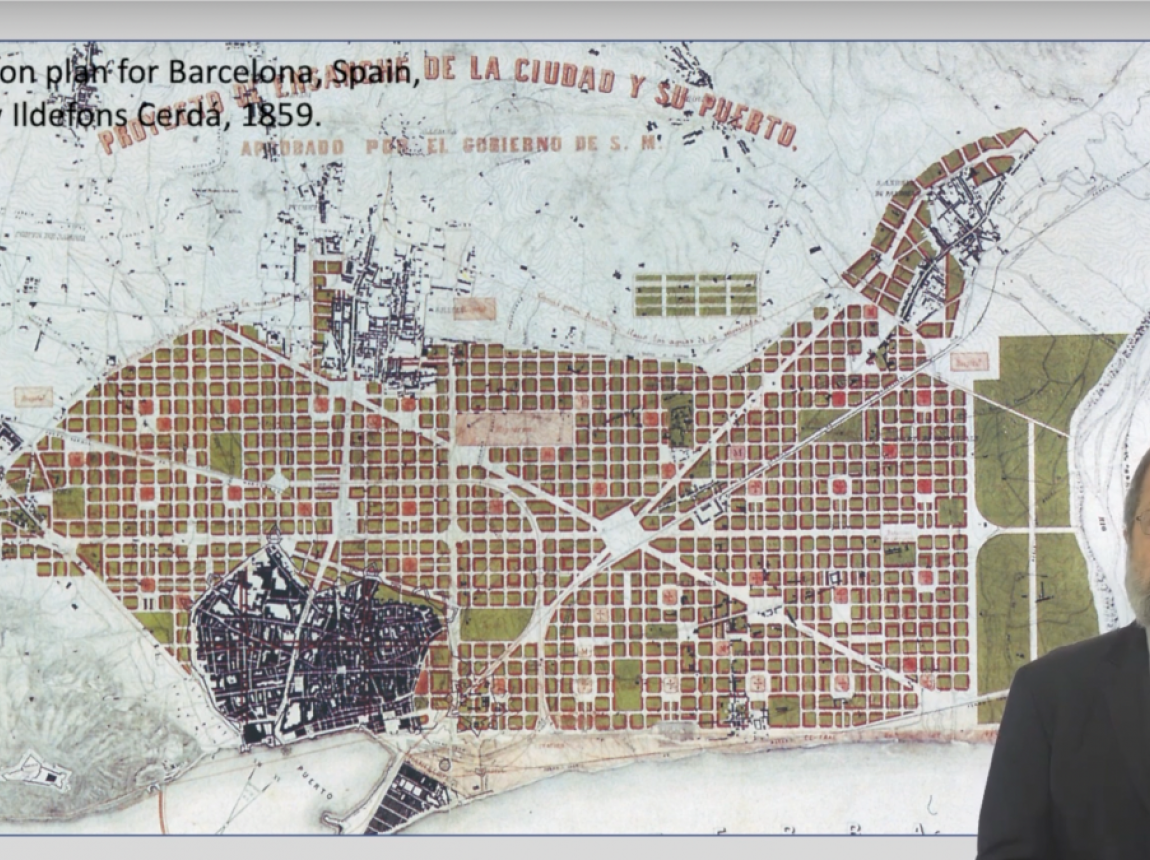

China’s Urban Planners

Could Determine the Future of City Life

Jonathan English

Offers Solutions for the Slow Spadina Streetcar

Jonathan English

on the Reasons for Depressing US Train Stations

Alon Levy Interviewed by The Wall Street Journal

Eric Goldwyn Calls on Zohran Mamdani

to Rethink Free Bus Pledges

Could Cable Cars Help

Fix Traffic Problems in Canada?

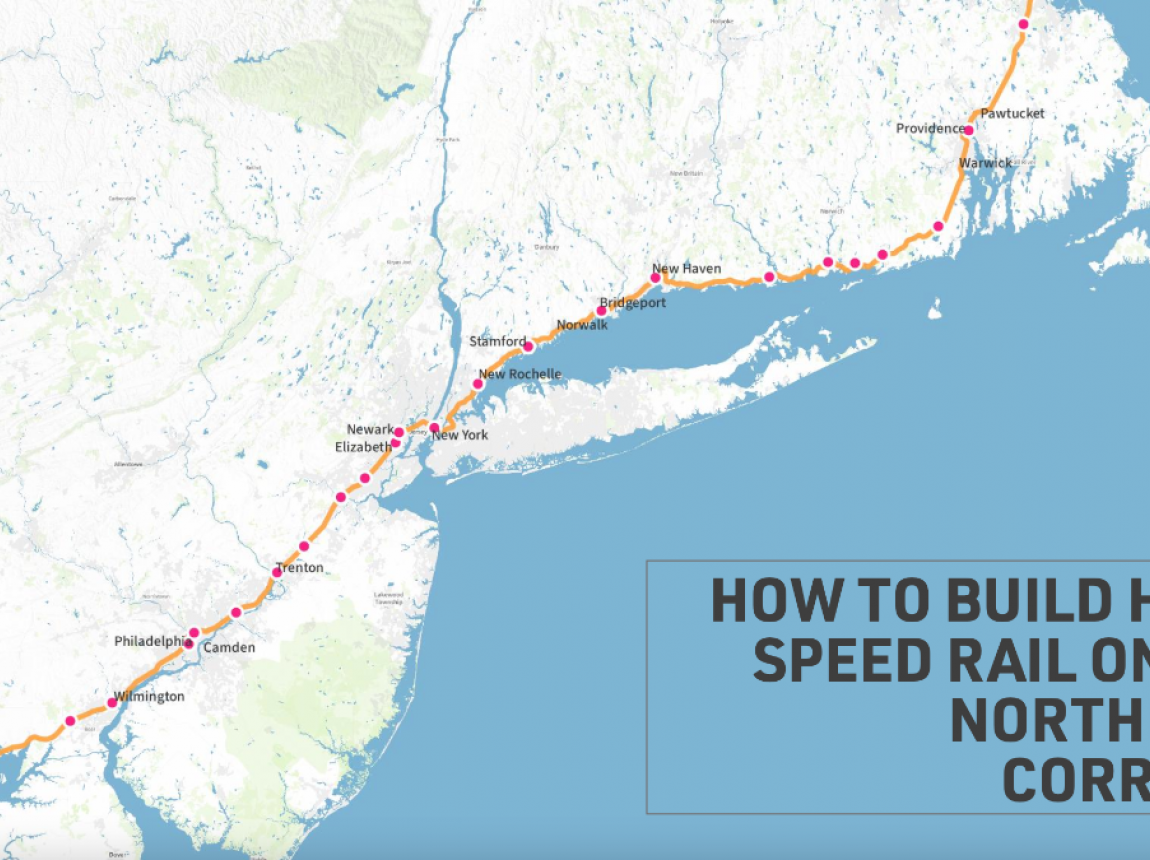

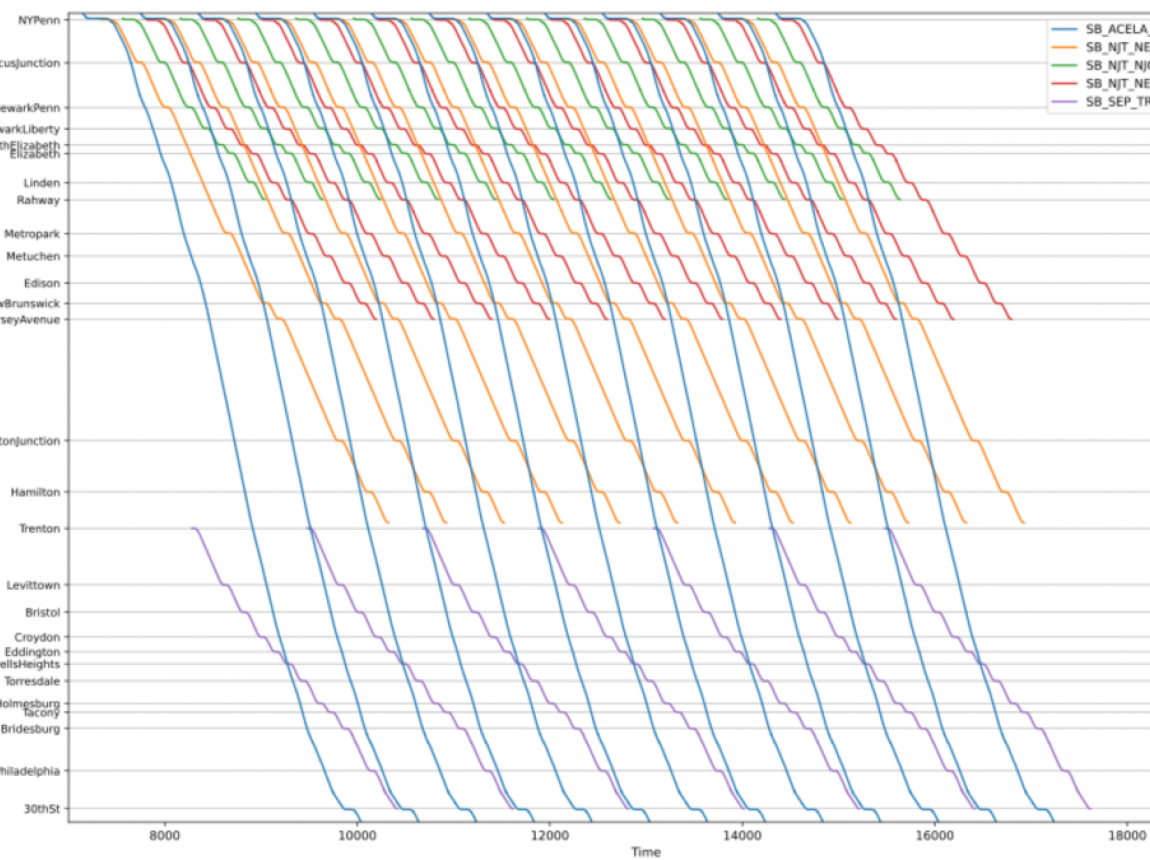

Will Amtrak Ever Improve

Its Northeast Corridor through Providence? Where It Stands.

As New York City Debates Free Buses,

Westchester County Cracks Down on Fare Evasion

The $130 Billion Train That Couldn’t

Finances and Laws Complicate

Cuomo’s City Transit System Proposal

Ahead of Planned $7.6B Subway Car Buy,

MTA Looks Abroad for Lessons

Children, Youth and Families Conference

Hosted by Dallas County Court Services

Jonathan English

on the High Cost of Canadian Elevators