The Chicago Ceasefire

+

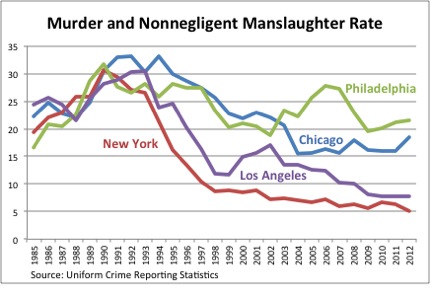

Over the last 20 years, crime rates, and homicide rates in particular, have fallen dramatically across US cities. However, as the attached graph of homicide rates shows, this drop has not been uniform across US cities. While Chicago experienced a drop in homicides in the second half of the 1990s, its drop was slower than that of either New York or Los Angeles. Chicago’s homicides then leveled out in 2004 at a rate substantially higher than New York or Los Angeles, though still lower than some other cities, such as Philadelphia.

An article by John Buntin details Chicago’s homicide problem, which is largely a gang problem. He reports that the city has approximately 100K gang members, and “Chicago Police Department officials estimate that 50 to 80 percent of the city’s shooting and murders are gang-related.” In addition to more traditional methods of policing, the Chicago Police Department (CPD) is also implementing a more novel approach to gang homicides: Operation Ceasefire. David Kennedy first developed this approach in Boston, and he detailed the concept and its history in his book Don’t Shoot. Buntin explains of Chicago’s Operation Ceasefire:

In response to a surge in youth violence, an interagency group there mapped gang feuds and identified the most active players. The group then called those gang members in for meetings with police, probation officers, prosecutors, gang workers and social service agency representatives to deliver a message: “We know who you are. We want to help you stop shooting. If you don’t, we’re coming after you.”

Part of what makes this approach powerful is the singular focus on violence. The interagency group will not go after gangs if, for example, only drugs are involved. Only violence warrants their attention. This narrow commitment means that they don’t make promises they can't deliver. Additionally, holding the entire gang responsible for the actions of each of its member is also important. If one hothead shoots his gun, everyone pays. Gangs therefore have an incentive to apply social pressure on individuals to not resort to violence.

Chicago’s Operation Ceasefire uses social media to improve network analysis and to focus on potential criminals:

...the CPD is mapping the relationships among Chicago’s 14,000 most active gang members. It’s also ranking how likely those people are to be involved in a homicide, either as victims or offenders. In the process, the CPD has discovered something striking: Cities don’t so much have “hot spots” as “hot people.”…People who were friends or friends of friends with homicide victims were approximately 100 times more likely to be involved in a future homicide than people who weren’t. Moreover, the people within this network appeared as future homicide victims and offenders at roughly equal rates. They weren’t perpetrators or victims. They were both…People who had been arrested within the previous five years were 50 percent more likely to be killed than people who were not arrested during that period…The homicide rate for that group was a shocking 554 per 100,000, or 900 percent higher than the average Chicagoan.

In Chicago, law enforcement representatives reach out to the “hottest” of these potential criminals and explain to them and to their “influentials" – people who are important to them and who might be able to encourage them to change their behavior – that they are on a police watch list. They further explain that additional convictions will likely come with higher consequences, such as federal prosecution and a lengthy prison sentence. Often influentials aren’t aware of the person’s behavior and the serious legal consequences for further infractions. Sometimes even the criminals themselves are aware of their precarious situation. Social pressure is, therefore, combined with a clear enunciation of the costs of additional criminal activity, hopefully compelling the criminal to change his or her behavior. Of course, not every criminal changes his ways and turns his life around, but this nudge can be exactly what some people need. Something in Chicago is definitely working: in the first 11 months of 2013, there were 393 homicides, compared to 492 at the same point last year.