Return to Sender

+ Brandon Fuller

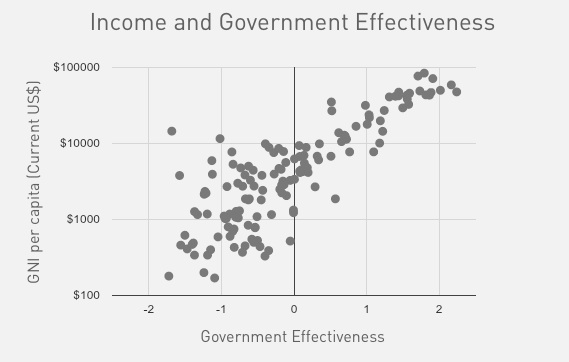

The quality of government tends to improve with growth in per capita income. The chart below shows income per capita for 166 countries in 2010 plotted against a Government Effectiveness score, one of the World Bank’s World Governance Indicators.

In a recent working paper Alberto Chong, Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de-Salines, and Andrei Shleifer suggest two broad explanations for this relationship. Politics: increasing incomes correspond with greater political voice and more accountable and responsive government. And productivity: rising incomes correspond with productivity improvements in both the public and private sectors.

To explore the productivity explanation, the authors offer a new indicator of government efficiency, postal efficiency. Unlike most indicators of government quality, this indicator relies on what government does rather than what survey respondents say. To measure postal efficiency, they sent letters to non-existent business addresses in 159 countries that subscribe to an international postal convention that requires the return of letters posted to an incorrect address. They then measured whether the letters came back and how long it took.

Postal efficiency is correlated with a country’s income and education levels, as well as survey-based measures of government quality. The results suggest that postal performance is related to factors that influence productivity in the private sector. Differences in inputs, such as postal staff per capita, and technology, such as a country’s postal code data base, help to explain variation in postal efficiency across countries. Management practices mattered as well. For example, a postal service that lacks sufficient monitoring or performance-based incentives is vulnerable to absenteeism, shirking, and delays.

If poor management practices contribute to low quality government, one question is how to improve them (provided politics aren’t standing in the way). The authors note that, in more developed countries, the public sector can hire better trained managers, those who can put a system in place that measures performance and periodically holds people accountable. This is one way to interpret the policing turn around in New York City. Improved policing had more to do with the introduction of better management practices under CompStat than with any specific policing strategy such as zero tolerance or hot spot policing. By simply raising the percentage of police officers who do their job, better monitoring led to better performance.

Some countries may be able to improve public sector management practices by looking outside their national borders. Working with allies or organizations that have a track record of good public sector management practices can be advantageous. The successes that Bulgaria, Anglola and Mozambique had after outsourcing their customs management to Crown Agents are cases in point.