Related

Feb 06,2013

Reducing Drug Trafficking Violence in Mexico

by

Brandon Fuller

Jul 26,2012

Police Reform in New Orleans

by

Brandon Fuller

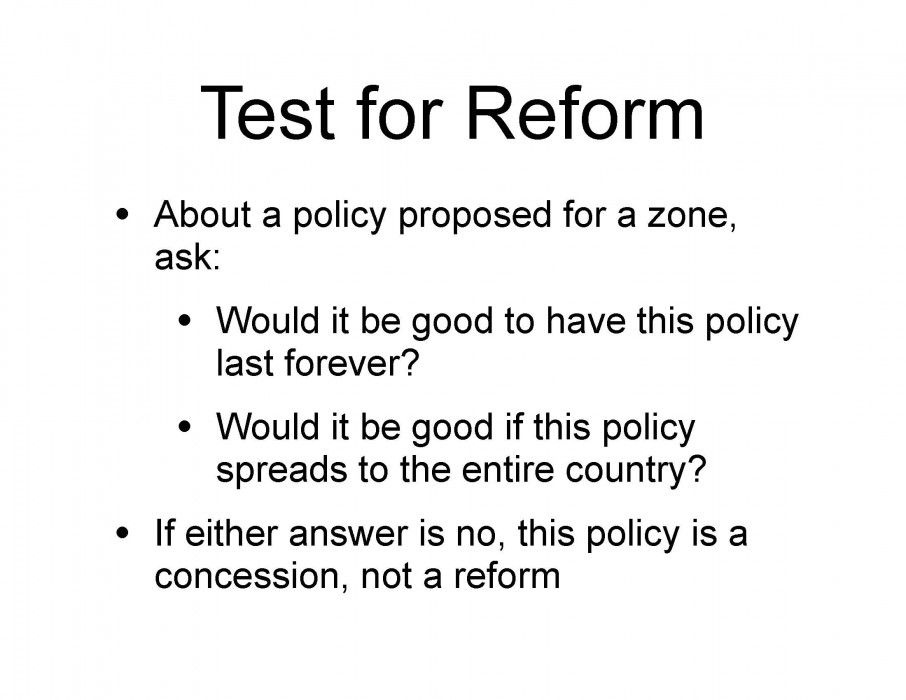

Because the new government in El Salvador might propose special zones as part of its economic strategy, ANEP, the local business association, asked me to give a talk about zones on June 23, 2014. The graphic conveys the main question I encouraged them to ask: Is a proposed zone being used to offer concessions or to give people a chance to opt into true reforms?

Because I do not speak Spanish and wanted to avoid any misunderstanding, I put everything I wanted to say as text on the slides. Find the complete slide deck here.

After giving the talk, I made one substantive change on the slide titled “Separation of Powers.” This slide suggests that in a special “low-crime” zone, laws could be enforced by using imported government policing and judicial services. Under this arrangement, the legislature in El Salvador could still pass the laws that apply throughout the country. In response to comments I received after the talk, I added a bullet point noting that under such an arrangement, the Supreme Court of El Salvador could adjudicate any constitutional questions even if foreign courts handled other judicial matters that arise in the special zone.

The key point is that a country can be selective when it imports government services into a zone. In terms of the usual notion of a separation of powers, it could keep some powers as a local responsibility and rely on imported government services to handle others. One advantage that imported services could offer would be to provide for politically neutral administration of criminal and civil justice even as the legislative decisions about the laws that apply throughout the country are resolved through a local political process.

During informal discussions at the ANEP meeting, some business leaders expressed concern about harm associated with uncertainty about legislative policy in a country that is still sharply divided about the role of the government in economic activity. They hoped for a zone where even legislative policy could be removed from local control. I responded that there is no way to resolve disagreements about the laws that should prevail in a country or a zone other than through the local political process. Rather than trying to use a zone to short-circuit that process, it might be better to use one to create an environment in which everyone could feel safe as they use the political process to work toward a durable policy consensus.

An analogy I invoked was the comparable divide in Great Britain after WWII between the Labour party and the Tories. It took decades of debate and experience with various policies to reach the current consensus about the appropriate role of state in economic activity. While this process played out, people in Britain enjoyed a crucial advantage that is not available to people in El Salvador. In Great Britain, centuries of experience with the rule of law ensured that the police and the courts would stay neutral in the contest between Labour and the Tories.

It is likely going to take time for the political process in El Salvador to come to a comparable consensus about the role of the state in economic activity. As this debate unfolds, it might be useful to find a way to give Salvadorans a chance to opt into a comparable level of protection by police and courts that enforces in a neutral fashion the laws the legislature enacts.

The danger for all political parties is that one of them could use its control of the executive and judicial branches to undermine fair political competition. People in some countries seem to hobble their courts and police because ones that were effective could tempt abuse by political parties. Even a party that truly believes in non-interference in the judicial system might feel compelled to violate this belief if doing so prevents another party from acting first and undermining the rule of law to an even greater extent. For this reason, it can be profoundly destabilizing to create a powerful judicial system and then to leave its control up for grabs in a local political contest because the norms that support judicial independence have not had time to take root.

In these circumstances, foreign governments can help if they can make a more credible commitment to neutral administration of police and courts than any domestic party can make until these norms are well established.

In my talk, I did not take the time to acknowledge the inherently political nature of the power granted to a Supreme Court to challenge the constitutionality of laws adopted by the legislature. Supreme Courts are participants in the legislative process. There is no way around the fact that they “legislate from the bench” when they rule that a law is unconstitutional. This was the issue that drove some members of the British Commonwealth to abandon the system that Mauritius has retained in which the Privy Council in England acts as the court of final appeal even on constitutional questions. Legislatures in some of these countries enacted a death penalty that the Privy Council refused to enforce.

On such deeply political decisions as the status of capital punishment or the circumstances in which it is legal to terminate a pregnancy, it makes sense to include the power of constitutional review as part of the system that determines the laws that apply in a country and should therefore remain under local control. This can be separated from the other types of review undertaken by the judicial system.

This is a particularly easy recommendation in El Salvador. Its supreme court is widely acknowledged to have exercised a principled check on the legislative and executive branches. It has provided stability and reassurance to a country that is still recovering from the political violence of its civil war years, 1979-1992. It is a role that could and should be preserved in any new arrangement designed to address the new challenge of controlling criminal violence.

Tile image courtesy of Ariel Dovas.

Please fill out the information below to receive our e-newsletter(s).

*Indicates required.