Drug Offenders in U.S. Prisons

An International Comparison

+ Keith Humphreys

A bipartisan group of Senators is pushing for the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act to receive a floor vote following its passage through the Judiciary Committee in October. The bill lowers penalties for many drug-related offenses while toughening penalties for violent crimes. Is that the right formula for moving away from mass incarceration?

Even though the United States’ imprisonment rate has fallen to a level not seen since 2001, it remains among the highest in the world. The most popular explanation for the U.S.’s relatively high imprisonment rate, put forward by Presidential candidates and best-selling books, is the ferocity of its drug law enforcement. Southern European Countries that decriminalized all drug possession – most notably Portugal – are believed by many people to offer an alternative policy approach that would result in prison being reserved mainly for offenders serving time for armed robbery, rape, homicide and other serious non-drug-related crimes. But the truth is more complicated according to an analysis of international prison data by Carnegie Mellon University Professor Jonathan Caulkins and University of Maryland Professor Peter Reuter.

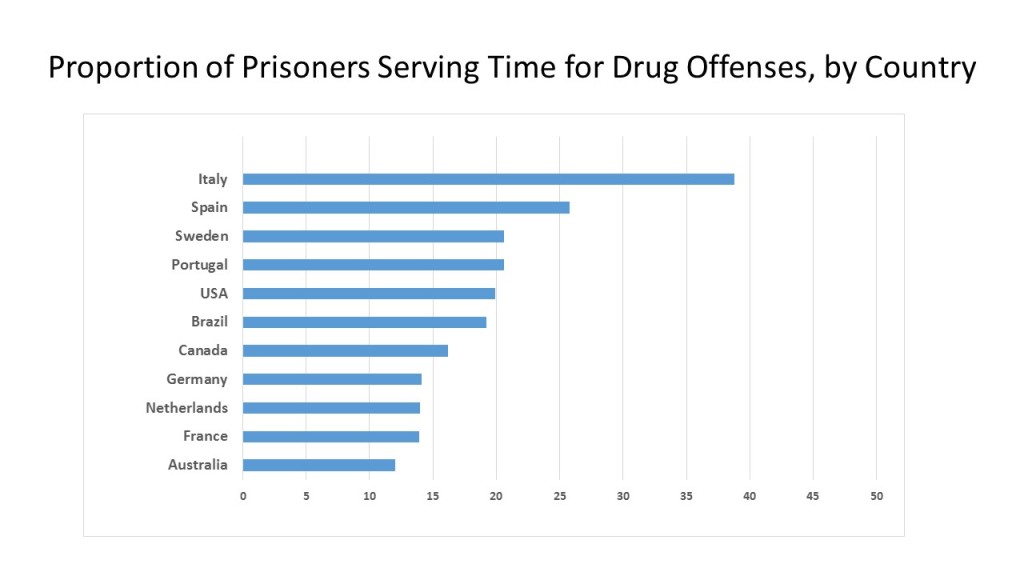

Remarkably, the United States and Portugal have virtually identical proportions of drug offenders among their prisoners, about 1 in 5. In Spain and Italy, which also decriminalized all drug possession, drug offenders are a substantially higher proportion of the prison population than in the U.S. The U.S. thus stands out internationally for having a huge prison population but not for being particularly prone to incarcerate drug offenders. This remarkable situation results from two factors that make the U.S. unique in the Western Developed World.

First, the U.S. has tough punishments for crime across the board, not just for drug offenses. Second and contributing to the first, the U.S. is a shockingly violent country by international standards. Over the past century, the U.S. homicide rate has consistently been many times that of Western Europe. To state the obvious, murder outrages and terrifies people, creating a political constituency for tough punishments for violence. In a nation that lengthens prison sentences while suffering through decades of high violent crime rates, the bulk of prison cells are going to be filled with people convicted of violent crimes rather than drug offenses.

Now that the U.S. crime wave has subsided, many states have taken advantage by reducing criminal penalties and investing in rehabilitation programs. For such reforms to make a big dent in mass incarceration, they will have to go beyond drug offenders to the 80% of prisoners incarcerated for other crimes (primarily violent ones).

Yet the federal prison system, which Congress oversees, is a unique animal within the U.S. correctional system. Most of its inmates are not violent, and almost half are serving time for drug-related offenses. In the state prisons which house about 7 in every 8 U.S. inmates, increasing sentences for violent crimes while curbing penalties for drug offenses would likely worsen mass incarceration. But in the small, atypical federal prison system, the Senate’s approach should have the opposite effect and thereby contribute to the nation’s ongoing reversal of mass incarceration.

This article is cross-posted from The Reality Based Community.