Related

Event

/ Mar 11,2023

NYU New Cities Conference

Innovative Approaches for Urban Transformation in the Global South

Dec 04,2012

Alain Bertaud on Urban Utopia

by

Brandon Fuller

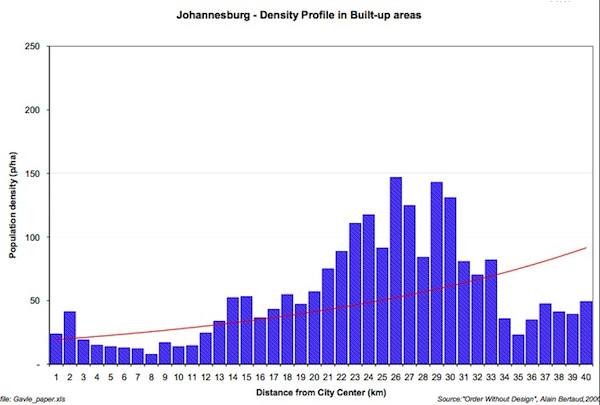

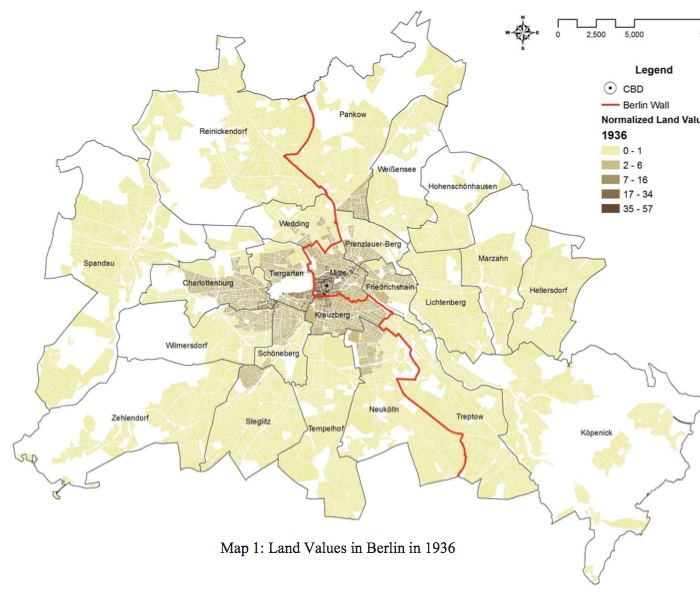

How did the division of Berlin after World War II affect land prices and economic activity in West Berlin? And what does this tell us about the underlying forces that drive land values and the concentration of economic activity in cities? These are a couple of the questions that Gabriel Ahlfeldt, Stephen Redding, and Daniel Sturm, and Nikolaus Wolf set out to answer in an interesting new discussion paper. They examine land values and employment concentration in West Berlin in the pre-war period (1936), during the division of the city (1986), and after reunification (2006).

Though Berlin was located well within the boundary of Soviet-occupied East Germany, an autumn 1944 agreement between the Allies assigned more than half of the city’s area to British, American, and French sectors — sectors that ended up comprising West Berlin during the Cold War. Initially the boundary between East and West Berlin remained open but the resulting flow of refugees from East to West led the East Germany authorities to construct the Berlin Wall in 1961, ending all local economic interactions between East and West Berlin.

The division separated West Berlin from what had been the commercial heart of pre-war Berlin, the Mitte district. As the map of land values in 1936 implies, Mitte contained the highest pre-war concentration of employment and residents of any district in Berlin. To the extent that districts in West Berlin experienced benefits from proximity to the Mitte district before the division, the construction of the Berlin Wall eliminated them. This put firms and residents in those proximate districts at a productive and consumptive disadvantage. Division meant fewer opportunities for West Berlin firms to share specialized inputs with firms in East Berlin; fewer opportunities for firms to find workers who fit well with their needs; fewer opportunities for firms and residents to exchange useful ideas; fewer opportunities for workers to find firms that fit well with their skills; and fewer leisure opportunities for consumers.

The authors found that this loss of access reduced land prices, employment, and population in West Berlin. What’s more, they found that these effects were stronger for the parts of West Berlin that were closest to Berlin’s pre-war commercial and residential concentration in the Mitte district. That is, land values declined most in the city blocks closest to the Wall.

The Berlin Wall also greatly reduced rail access from West Berlin to East Berlin and the East German hinterland. As a result, the value of locating a workplace or residence close to a train station declined and the areas of West Berlin closest to train stations experienced unusually large declines in land prices as well. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in the autumn of 1989 and the formal reunification of East and West Germany in the autumn of 1990, land values reversed course, increasing by larger margins in the city blocks closer to train stations and nearer what had been the Berlin Wall. The results are a useful illustration of the benefits and efficiencies that firms and people realize by interacting with one another in densely-settled urban areas.

Please fill out the information below to receive our e-newsletter(s).

*Indicates required.