Alain Bertaud on Urban Utopia

+ Brandon Fuller

In his 2001 paper “The Costs of Utopia,” UP scholar Alain Bertaud considered the spatial structures of Brasilia, Johannesburg, and Moscow—cities characterized by intrusive, ideology-driven urban planning. He contrasted them with the spatial structures of cities such as Paris and Washington, D.C. Though urban design clearly played an important role in the development of Paris and Washington, the approaches were lighter touch by comparison. They also left substantial room for market-driven development of private spaces compared to the utopian cities of Brasilia, Johannesburg, and Moscow.

Haussman did design street patterns in nineteen century Paris, so did L’Enfant in Washington. However, these “urbanists” only designed the boundaries between public and private use. They only allocated precise functions to public space: streets, avenues, parks, and public buildings. But they did not design the city in the sense that, with the exception of public monuments, they did not decide who was going to live where, they did not decide where offices and residential areas will be located and what should be the density in these areas. Market forces were left free to fill the bulk volumes allocated to private use.

In utopian cities, the role of markets in the development of private spaces is intentionally minimized or eliminated. Planners make and enforce specific prescriptions about land use and densities, as well as economic, social, and cultural development. In Brasilia, the spatial structure was defined by Lucio Costa, in Johannesburg by the apartheid government, and in Moscow by the Soviet bureaucracy. Though the ideologies informing the urban plans were very different, they led to very similar spatial outcomes.

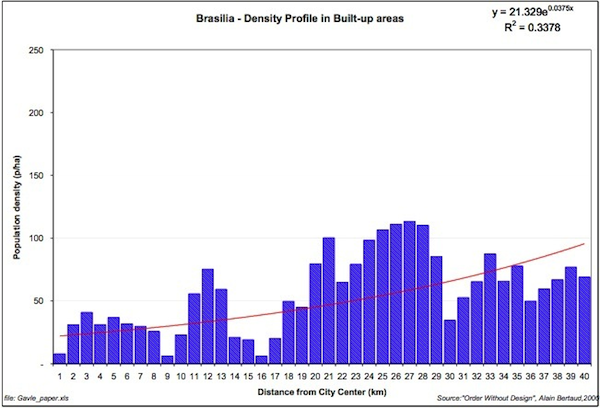

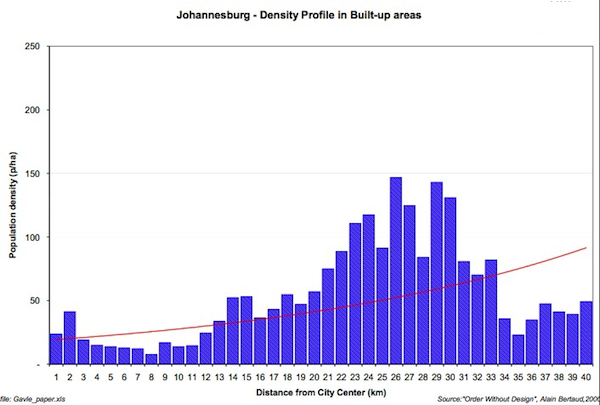

At the time Bertaud wrote the paper, each city had a positive density gradient. Densities in the three cities actually increased with distance from the city-center, the exact opposite of the typical outcome in a city such as Paris or Washington where land markets operated more freely. We’ve covered the reasons for Moscow’s positive density gradient in a previous post but the policies in Brasilia and Johannesburg are worth a look.

In Brasilia, the relatively low density at the city’s center reflected the elevation of design over practical concerns:

The entire city was entirely designed by the planner and a number of government appointed architects. No land values, rents or demand was considered. In this sense the main ideology that created Brasilia was a cult for design and a paternalistic attitude toward the masses. The land on which Brasilia was built was entirely acquired by the State and the construction of highways, government offices, shopping centers and housing was designed and built under direct government supervision without any market input.

The positive density gradient in Johannesburg reflected the strict geographical separation of people by race. White families lived in low-density housing developments near the center of the city or in farther away suburbs that were well served by highways. Black and mixed-race families were confined to crowded government-owned townships on the periphery of the city.

In addition to increasing density at the periphery, Bertaud also found that utopian cities tend to be more dispersed than their more market-driven counterparts. That is, compared to cities with similar areas, utopian cities put greater distance between the typical resident and the cities center of gravity.

Dispersion increases the operational cost of a city by increasing the length of networks. It also increases the use of energy for transport and as a consequence it increases also air pollution. One should note that there is no direct inverse correlation between density and dispersion, contrary to what is generally thought… Brasilia with more than twice the density of Los Angeles is three times more dispersed.

When planners suppress land markets, there’s no guarantee that jobs and commercial activity will be easily accessible from the land designated for housing, even if the housing developments themselves are relatively dense.

The full paper here (pdf), in which Bertaud assesses the experiences of the “lesser utopian” cities of Curitiba and Portland, is well worth reading. Find previous posts on Bertaud’s work here and here.