Related

The data presented here convinces me that policy-induced changes in the urban share of the population could have big effects on GDP per capita and could operate on a scale that affects the quality of life for billions of people. So in research on development policy, I am not persuaded that economists should narrow their focus to the analysis of such easily evaluated micro-initiatives as funding women’s self-help groups. Neither is Lant Pritchett.

In a characteristically incisive blog post, Lant expresses skepticism about the value of micro-initiatives that are being tried as strategies for encouraging economic development because they are easy to evaluate rather than because experience suggests that they have worked at a scale that is comparable to the problem that policy should address.

He recalls his experience as a member of a team with members from many developed countries that was evaluating a program in India that financed women’s self-help groups. A woman from West Bengal who had answered their questions said to the team, “You all are from countries that are much richer and doing much better than our country so your country’s women’s self-help groups must also be much better, tell us how women’s self-help groups work in your country.” Quoting now from Lant’s account:

We all looked at each other blankly as none of us had any idea whether there even were at any time in our countries’ history such a thing as “women’s self-help groups” … (much less government program for promoting them). We also had no idea how to explain that, yes, all of our countries are now developed but no, all of our countries did this without a major role from women’s self-help groups at any time (or if there were a role we development experts were collectively ignorant of it), but yes, women’s self-help groups promote development.

Pritchett proposes a basic, four part test that economists could consider when someone claims that governments or donors should experiment with policies designed to promote variable X because more X is good for development:

The historical question, #2, deserves a separate treatment. Here I’ll show that when we consider the urban share of the population as our candidate variable (without any attempt at correcting for the quality of urbanization) the data from many countries in the years from 1955 to 2010 give us confidence that the answer to questions 1, 3, and 4 is yes, more urbanization is associated with income per capita.

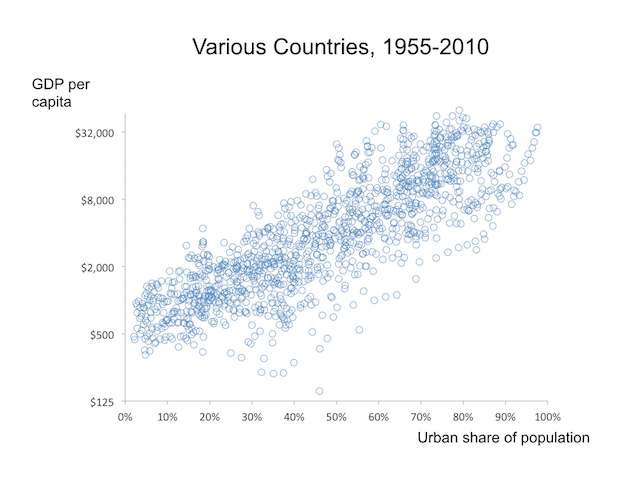

The first figure shows the urban share of the population and GDP per capita (measured on a log or ratio scale) every 5 years from 1955 to 2010 for all year-country pairs. The urban share data comes from the United Nations. GDP per capita come from the Penn World Table 8.0. The figure shows the strong correlation of urbanization with GDP per capita, but it does not split it into the cross-sectional and time-series components that Pritchett encourages us to consider separately.

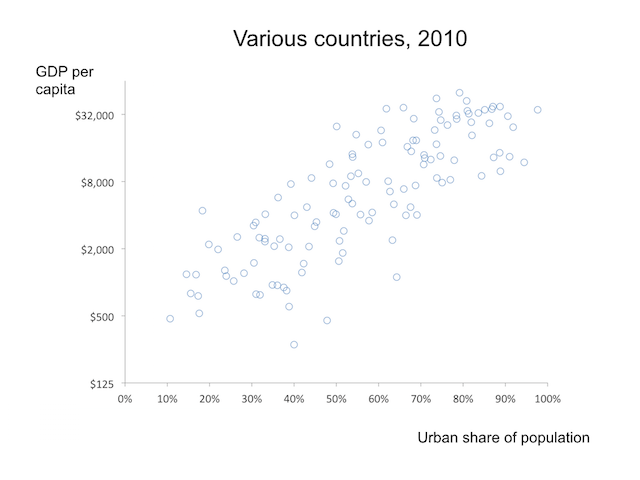

The second figure shows one simple way to get at the cross-sectional variation. It plots the urban share in 2010 against GDP per capita in that year.

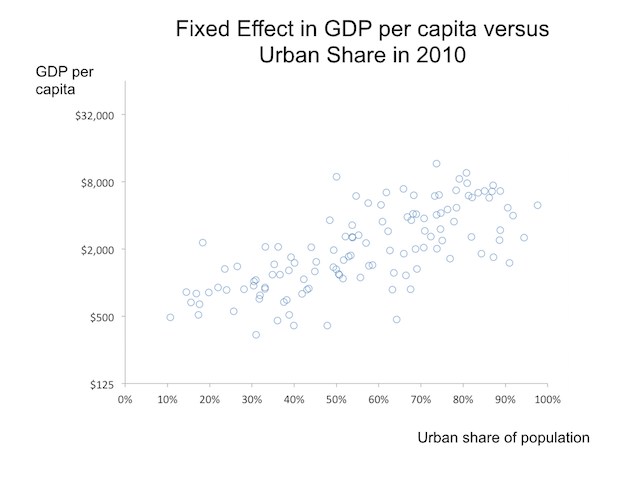

Figure 3 tries to make a correction for the fact that a country could end up with a high urban share and high GDP per capita in 2010 because over the last 55 years it experienced a rapid increase in both. (Figure 6 below shows that South Korea is an example of this type.) We might want to assign the outcome in an instance like this to the changes in the recent period rather than to a country specific effect that is derived from its history. One way to separate out the effect of the changes over time from the persistent differences between countries is to run a regression that allows for country-specific fixed effects (that is, a country dummy variable). Figure 3 plots the estimated country effect from a fixed-effects regression of GDP per capita on the country dummies, the urban share, and a time trend. As one might expect, the scatter plot of these country-specific effects has a slope that is less steep than the scatter of points in figures 1 and 2 because the regression allocates some of this correlation to the average of country-specific changes over time. But when examined this way, the data still show that the answer to Pritchett’s first question is unambiguously yes. In the variation across countries, urbanization and GDP per capita are positively correlated. This relationship in Figure 3 is quantitatively important and statistically significant: a 1% increase in the urban population share is associated with a 2.7% increase in GDP per capita, with a t-statistic of about 11.

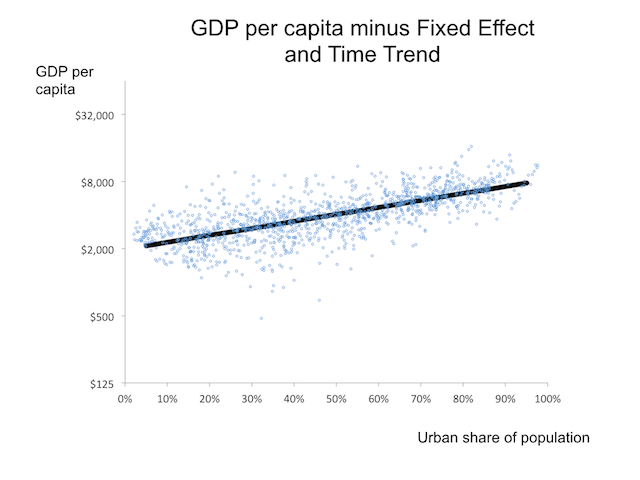

Figure 4 shows the correlation between the urban share in a given year and GDP per capita in that year after taking out the effect of the country specific dummy and the common time trend. The slope of the black line is the coefficient on the urban share in the fixed-effects regression. This slope is less than either of the slopes from figures 2 and 3, but it is still quantitatively important and statistically significant, with a value of about 1.4 with a t-statistic of about 6.

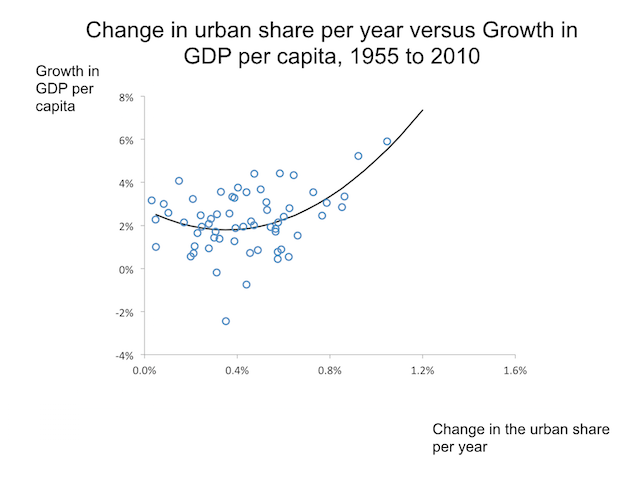

Figure 5 looks at the changes over time in a different way. For each country, over the interval 1955 to 2010, it shows the average change per year in the urban share and the average annual rate of growth of GDP per capita. As usual, this kind of relationship in differences is less tight than the corresponding relationship in levels, but the simple correlation is still positive, and a fitted curve that allows for constant plus a nonlinear relationship suggests that the association between the two is particularly strong for countries that experience a rapid growth in the urban share. So together, figures 4 and 5 suggest that countries that have a bigger increase in GDP per capita also tend to have a bigger increase in the urban population share.

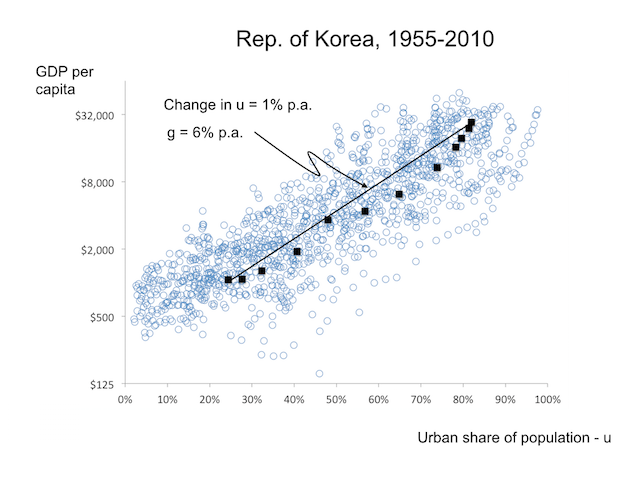

The last two figures address Pritchett’s fourth question: Does a country that experiences a big increase in the rate of growth of GDP per capita also experience a big change in the rate of increase in the urban share? South Korea stands out as the point in the extreme upper right of the scatter in figure 5. Figure 6 overlays its experience from 1955 to 2010 against the scatter plot from figure 1. As noted above, the overlay shows that for South Korea, the combination of high GDP per capita and high urbanization today reflects big changes in recent decades. The data over this interval do not allow a direct comparison between a slow growth and fast growth period, but they do suggest an indirect comparison with the period before 1955. Because South Korea starts in that year with such low levels of the urban share and GDP per capita, these two variables must have been growing more slowly in the 50 or 100 years prior to 1955.

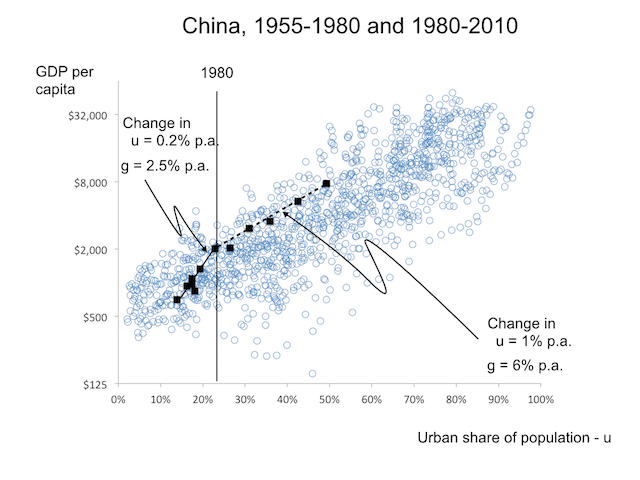

Figure 7 presents an overlay of the experience in China, which does offer a clear before-after comparison. The figure uses 1980, which is roughly the beginning of reform there, as the breakpoint. Before, the urban share increases at the rate of 0.2 percentage points per year. After, it increases by 1.0 percentage points per year. Before 1980, the growth rate of GDP per capita is 2.5% per year. After 1980, the growth rate is 6% per year.

So at least in a couple of notable cases, a big change in the rate of growth of GDP per capita was accompanied by a big increase in the rate of increase in the urban share.

There is much that economists and policy makers need to learn about the causal connections between GDP growth and growth in the urban share. It is also very important to understand which other complement faster and better urbanization. But because it passes the Pritchett test, urbanization deserves intensive practical analysis and careful but ambitious exploration and experimentation.

Humans already do things that overwhelm the imagination. For example, they manage to get food each day to the more than 3 billion people who already live in cities. The evidence here on the potential benefits from faster (and better) urbanization hint at the possibility if the right policies expanded those amazing things to a scale that is 2 to 3 times bigger, the quality of life could substantially improve for billions of people. These policies could give everyone on earth the chance to contribute to and benefit from the interactions that current urban residents already enjoy. The magnitude of what is at stake should not be used as an excuse for more study and delay. It should impel us forward.

Please fill out the information below to receive our e-newsletter(s).

*Indicates required.