Related

Nov 01,2023

Urban Expansion Program Hosts Malawian Dignitaries

for Accommodating Urban Growth Workshop at NYU Africa House

Dec 04,2012

Alain Bertaud on Urban Utopia

by

Brandon Fuller

We’re pleased to have Alain Bertaud on board at the NYU Stern Urbanization Project. This post is the second in a series of posts about some of his previous work. In his 2002 paper, ”Clearing the Air in Atlanta,” Bertaud asked whether traditional smart growth policies would be effective for reducing traffic congestion and pollution in Atlanta.

At the time, the Atlanta Regional Commission (ARC) envisioned a two-pronged strategy for reducing traffic: 1. invest in bus, light rail, and metro extension, and 2. change land use regulations to foster density, mixed use, and transit-oriented development.

The ARC plan rested on a couple of assumptions. First, demand for mass transit would rise if supply increased. Second, land use changes could make public transit a feasible alternative for a large share of residents. By challenging these assumptions, Bertaud’s paper casts doubt on the traffic reducing potential of the plan.

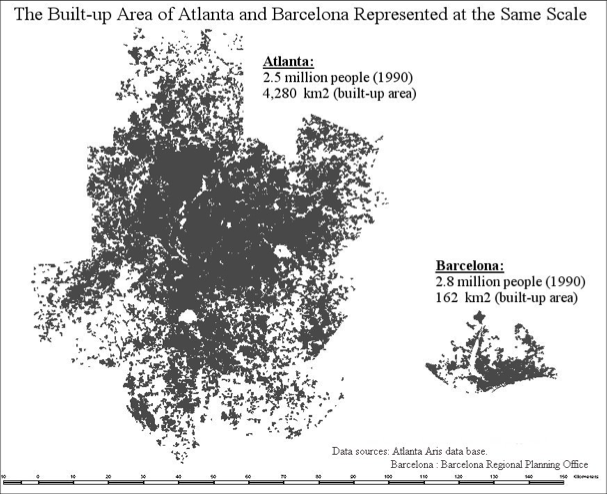

He points out that Atlanta’s spatial structure is exceptional. The city’s average built-up area density is very low, even by American standards. At the time, density in Atlanta was 6 people per hectare, less than a third of density in LA (22 p/ha) and incredibly low compared to a dense European city like Barcelona (171 p/ha).

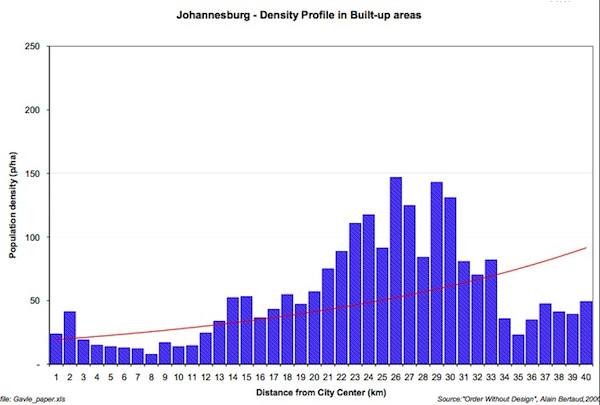

Bertaud also pointed to Atlanta’s relatively flat density profile—densities near the center of the city are only slightly higher than those 20 km away. A flat profile indicates that jobs and people are dispersed widely across the metropolitan area compared to cities like Barcelona where densities near the center city tend to be much higher than those further away. As can be seen in the graphic above, Atlanta’s low density and flat density profile lead to an urban spatial structure that is markedly different from Barcelona, a city that had a comparable population at the time.

The metro network in Barcelona is 99 kilometers long while 60% of the population lives at less than 600 meters from a metro station. Atlanta’s metro network is 74 km…but only 4% of the population live within from a metro station…

Suppose that the city of Atlanta would want to provide its population with the same metro accessibility that exists in Barcelona i.e. 60% of the population within 600 meters from a metro station. Atlanta would have to build an additional 3,400 kilometers of metro tracks and about 2,800 new metro stations. Such an enormous new capital investment would allow Atlanta metro to potentially transport the same number of people that Barcelona does with only 99 kilometers of tracks and 136 stations. In short, the effect of density on the viability of transit is not trivial.

If low density made a transit build-out infeasible, could increasing Atlanta’s density offer a path to viable transit? Bertaud points out that a density threshold of 30 p/ha can support intermediary bus service. To see if Atlanta could get from 6 to 30 p/ha he ran through two scenarios. Each one takes 4,280 sq km as the starting point for Atlanta’s built-up area and then assumes 3.14% population growth (the actual rate from 1990 – 2000) over a twenty year period.

The first scenario assumed that Atlanta reached 30 p/ha by 2010. To get there, Atlanta would have had to shrink it’s built-up area by 64%, from 4,280 sq km to 1,555 sq km. Clearly, that wasn’t going to happen. The second scenario assumed zero greenfield development and no shrinkage—additional population but no additional land. Under this scenario, density would have reached 11 p/ha by 2010, still well short of 30 p/ha threshold for bus service.

While Bertaud believed that modifying land use regulations would make Atlanta a more pleasant place to live, he concluded that the ARC plan could not have a meaningful impact on traffic congestion or pollution. Tackling those problems would require a different approach, an approach in which the city’s only serious policy option was congestion pricing:

Charging for highway use provides a strong incentive to increase vehicle occupancy and car pooling… It is possible that in the case of Atlanta, a decrease in congestion caused by tolls, combined with a higher cost for using a one passenger vehicle may boost some minibus transit traffic… Less congestion would also make the existing buses more competitive with cars for some trips in terms of cost. Because of the charges induced by car trips on highway, people would tend to drive less and consolidate their trips in order to save on tolls. It should also be noted that less congestion, i.e. higher speed, also means less pollution.

You can find Bertaud’s full paper here (pdf).

Please fill out the information below to receive our e-newsletter(s).

*Indicates required.