Housing in China: Large vs Small Cities

+ Paul Romer

One of the newsletters I follow on China is Dragonomics, from GK Research. The head of research there, Arthur Kroeber, has a good command of economic theory but still shows his roots in journalism. His shop seems to stay close to the facts as best they can establish them, with little concern about a theoretical framework into which they must fit and little concern for whatever the fashion of the day happens to be: "China is unstoppable. No, wait, China is crashing. No, wait it's unstoppable...”

A recent article, Small is Not So Beautiful (made available here by permission), shows that the state of the housing market in China is very different in different types of cities.

Since 2008, population growth has increased in the four big cities (Beijing, Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Shenzhen) and in such second tier cities as Chongqin, Dalian, and Fuzhou. At the same time, population growth in the tier 3 and tier 4 cities has slowed. The tier 3 and 4 cities are also the ones where the supply of housing has been growing fastest.

The author concludes that for the country as a whole, the housing market has turned soft but that this is not evident in the official series on housing prices, which relies on data from only the 70 largest cities. (Let that sink in for a moment. "Only the 70 largest cities." Everything about China leads to bigger numbers than the ones we are used to.) So despite the strong prices that we see in the largest cities, housing construction for the nation as a whole may slow. If so, this will pose a potential problem for short-run growth.

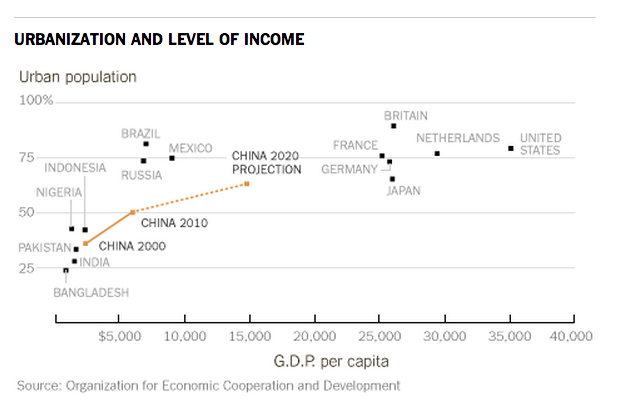

The fact that people increasingly want to move to the biggest cities where housing is most expensive tells us something important about the productivity advantages of those cities. If there are government policies that are limiting the growth of housing in its biggest cities, these should be removed. Most countries, including the US, impose these kinds of limits on population growth in their biggest cities. China could leapfrog them by following the market and letting the supply of housing in all cities respond to demand. Moreover, as the author hints, doing so now might be a good way stave off what might otherwise be a decrease in housing investment for the country as a whole.

But if we take the limitations on the supply of new housing in the biggest cities as a given that can't be changed, it does not follow that the right policy is to limit supply in the small cities as well. Anywhere in the country, additional housing units help address the problem of housing affordability. In equilibrium, a less expensive apartment in a smaller city may be less attractive as a real estate investment. Wages in the small cities might also be lower than in the bigger cities. But after adjusting for the lower cost of housing, the quality of life in the smaller cities might be higher, particularly for young people for whom a down payment on an apartment is required before they can get married and start a family.

If governments impose restrictions on the supply of housing in the biggest and most attractive cities, this will impose an efficiency cost because it diverts workers from the cities where they would be most productive. But if we take the limitations on housing supply in Shanghai and New York or in Beijing and San Francisco as given, it does not follow that allowing unrestricted investment in housing in other cities is a mistake. China should be careful to avoid the boom-bust cycle of Las Vegas, but there is no reason why it can't have its own Houston.

So even if prices for apartments in the smaller cities stay constant at close to their cost of construction, the best policy might be for the government to give free reign to any entity that wants to supply new units of housing in those smaller cities. The US has managed to live with large persistent differences in the price of housing between a market such as Houston and markets with supply restrictions such as New York and San Francisco. There is no reason why China can't do so as well.