Ben Mandel on Crime, House Prices, and Inequality in Rio

Benjamin Mandel of Citi Research recently presented joint work with Claudio Frischtak on policing, crime, and property values in Rio. For the past several decades, Rio’s high crime levels have been fueled by the drug trade and sustained by corruption among the police and political officials. Rio’s drug gangs were so powerful that for much of the last few decades they had de facto control in many of the city’s poor neighborhoods, or favelas.

In 2008, with the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics on the horizon, a new state government set out to bring Rio's crime under control. The effort focuses Police Pacification Units (UPPs) on reducing crime in a selection of Rio neighborhoods, including favelas, and it has coincided with falling crime rates city-wide.

Before entering a neighborhood, the police publicized their intentions up to six months in advance. Additional public announcements occurred approximately one month and 1-2 weeks before an operation began. On the designated date, an elite police force secures the neighborhood. Because the threat of entry is credible, drug gangs often prefer to vacate target neighborhoods rather than make a stand against the elite police forces. Driving the drug gangs out of favelas has therefore occurred with relatively low levels of violence and, importantly, low levels of disruptions to residents.

The elite forces gave the state time to build permanent police stations. Once built, new stations were staffed with newly hired and trained police officers. The decision to use new recruits was deliberate. Police corruption routinely undermined previous efforts to reduce crime and eliminate violent drug gangs. New recruits in new police stations can a new culture that is free of the corrosive influence of older, corrupted police officers. The new recruits miss out on some of the learning that occurs from operating alongside honest and more experienced officers, but proximity to the elite squads who initially command the UPPs may partially make up for this.

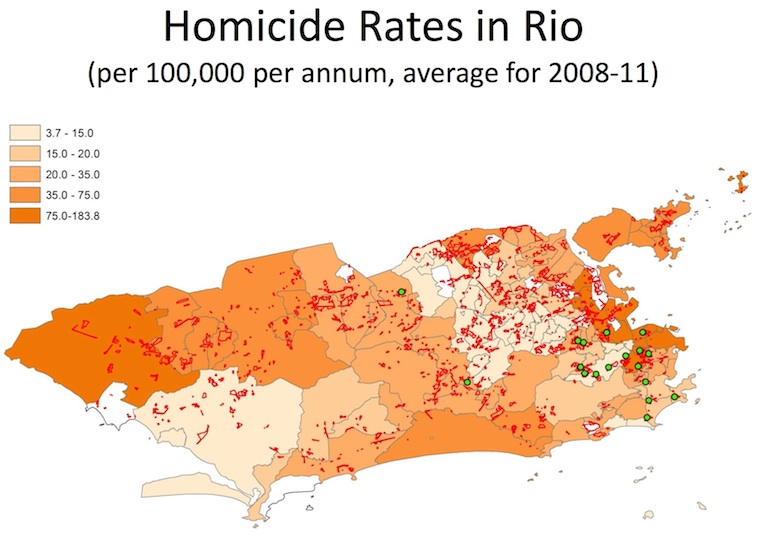

Though the decision to locate the UPPs was not random, they still make for an interesting natural experiment. The government’s decision to locate UPP’s was not based primarily on crime rates or related variables such as population density or property values. Instead, UPP locations were largely driven by the locations of facilities for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics. Though some favelas were singled out due to high crime, mapping the locations of the UPPs (the green dots in the map below) shows that they were placed in both high and low crime neighborhoods.

Frischtak and Mandel find that UPP stations lead to lower crime rates and higher property prices. Sale prices of nearby houses and apartments rise by an average of 5-10 percent. Neighborhood robberies decline by an average of 10-20 percent; homicides decline by an average of 10-25 percent. They estimate that the UPPs account for about 14% of the reduction in homicides since 2009 and 15% of the growth in overall house prices since 2008. What’s more, the crime declines associated with UPPs have a bigger impact on lower priced residences than higher priced residences. This narrows the distribution of house prices near UPPs and reduces disparities in wealth.

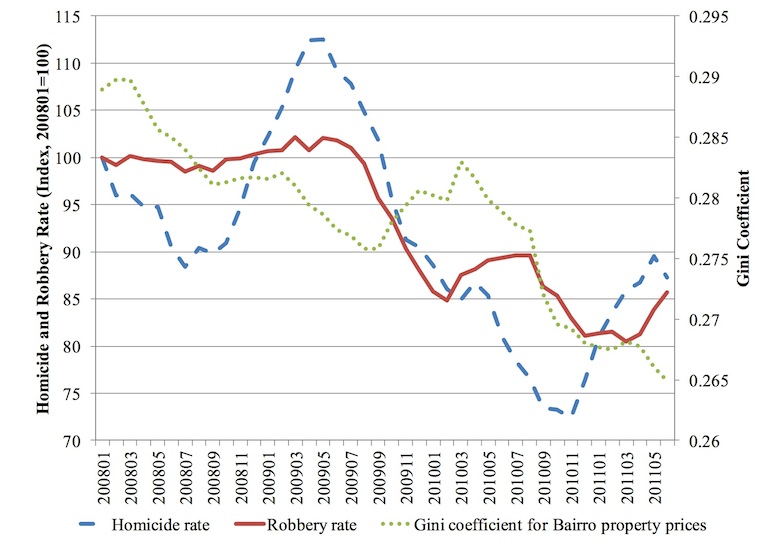

The figure above shows reductions in citywide homicide and robbery rates as well as the decline in property price inequality. Rio has continued adding UPPs since Frischtak and Mandel completed their study, and Rio’s crime rate has continued to decline. The paper provides further evidence that competent policing can reduce crime and enhance the economic well-being of urban residents—an encouraging result for cities, like Detroit and New Orleans, working to reform policing and boost economic activity.

Find an earlier version of Ben and Claudio's working paper here.

Speakers

Benjamin R. Mandel is an Adjunct Faculty Member at NYU Stern and a member of the Global Economics team of Citi Research. He focuses primarily on international economics and the effects of the global economy on the United States. Prior to joining Citi, Ben was an economist at the New York Fed, where he covered the Japanese economy, and an economist at the Federal Reserve Board, focusing on U.S. international trade.

Please fill out the information below to receive our e-newsletter(s).

*Indicates required.